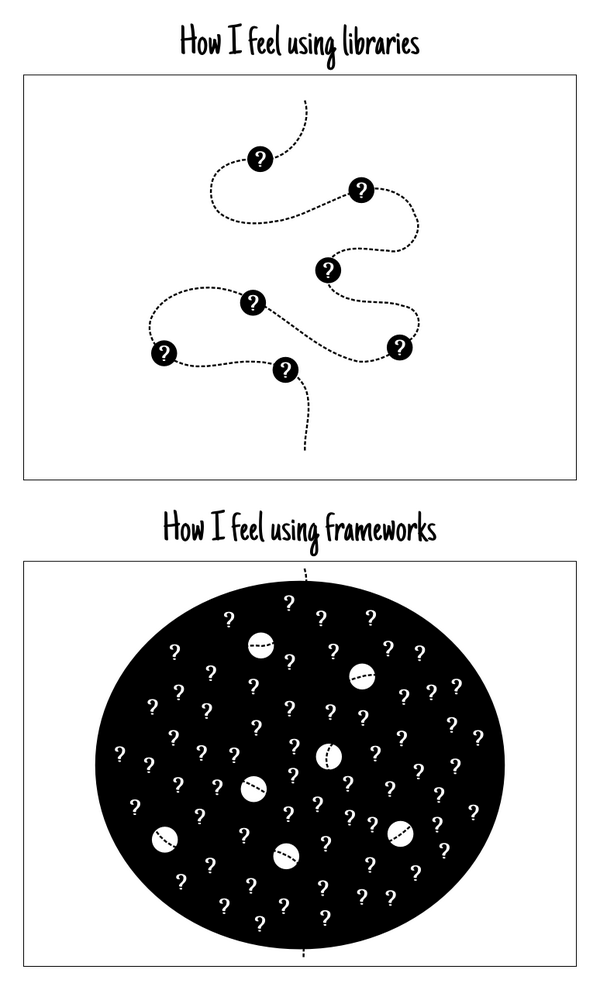

Jake Archibald tweeted this comic expressing (I’m interpreting here):

- There’s a difference between “using libraries” and “using frameworks”

- Even if you don’t understand the components themselves, when using libraries:

- there are fewer components in the system

- the program flow through the components is clearer

I believe this is completely accurate, in that a lot of developers feel this way about frameworks, but I don’t think it’s due to a big difference between using libraries vs. a framework. I think it’s rather a matter what kind of environments make developers happy.

Devs prefer a higher familiarity with the codebase

If you write an application “using libraries” it will always feel more comfortable. It will be crafted around your biases (your preferred configuration format and form, file layout, DI and other libraries, etc.) and it will be simple enough to meet just the use cases you foresee at the moment. Over time added features will force you to make more decisions about new components and refactoring. But no doubt you will have written a framework. Did you make objectively better decisions than those working on Framework (a public project that calls itself a “framework”), who maybe were also building on top of libraries? Maybe, maybe not, but you’ll probably feel better about those decisions, and when you look at the more complex code, you’ll remember why that code was needed and forgive the complexity.

But a new developer on this project won’t have the same biases, she’ll be overwhelmed by those complexities (which look unnecessary), and to her it will feel just like a Framework.

Code hosting sites are littered with skeleton apps built from libraries that have little or no documentation and would be difficult for a developer without the same biases to jump into. And every use case that’s had to be added has made those frameworks more complex and more impenetrable. At a certain level everything starts to look like Symfony, but frequently without the documentation and support community. An author that builds something such that the choices made were obvious may be less motivated to document it.

Devs prefer less complex systems that do a few things really well.

Large organizations maintain a variety of enterprisey apps like PeopleSoft that do 1E9 things to support 1,000s of business processes, and I feel for the folks “toiling in the Java mines” on these systems; it looks like messy, unglamorous work, and where each new feature has an impact on dozens of others. I think the sheer size of some Frameworks remind developers of these kind of nightmare scenarios.

Smaller projects with fewer use cases always enable a simpler framework around the business logic, and so any Framework that you’re not already very familiar with is going to seem like overkill. And it will be right up to the point where the project becomes complex or the original authors leave the team.

What to make of this

I guess my point is that, all code quality being equal and over time, there’s not a big objective quality difference between the framework you rolled from libraries vs the one downloaded that others rolled from libraries. But I recognize that its subjectively enjoyable to build them and to work on systems where you’re productive. And that matters.

Sorta-related aside: There’s an interesting tug-of-war dynamic between developers and management tasked with keeping a piece of software maintained. A lot of the web is geared towards hastily building something sexy and throwing it away if the product doesn’t take off, and so you want devs to create and use whatever they’re most productive in. But if you’re maintaining an internal business app that will certainly be critical for the foreseeable future—and one that devs will not tolerate working on it for long!—you have to optimize your dev processes for developer turnover, while simultaneously trying to keep them happy. Introducing any technology with a potentially short lifespan introduces big risk.